Sacred time, sacred space: ceremony and celebration in Pantheism

Practice of scientific pantheism* by Paul Harrison.

Pantheist ceremony celebrates the universe and nature,

and reminds us of our place in them.

Rocks, sea and sun, St Agnes, Scilly Islands. Photo: Paul Harrison.

The function of traditional ritual.

Ritual and ceremony are found in almost all the world's religions.

Usually they celebrate seasons of the year, times of the agricultural

cycle,

transitions in human life, or days of significance in the history of

nation

or

religion. They are usually symbolic, and follow fixed forms prescribed

by

tradition.Rituals have many functions. They cement the bonds of a society or community. They allay anxiety in a hostile universe. They provide the support of others for religious faith.

But in most religions they also have more primitive and selfish goals, similar to magic. Prayer invokes the help of invisible beings. Sacrifice and offerings try to control fate or to ward off the anger of the god or gods. Communion tries to acquire some of the magical power of the deity. All ritual acts may be thought to help in achieving a favourable afterlife.

Among the more sophisticated, ritual also has more noble functions: to remind people of their fundamental beliefs on a regular basis, and to acknowledge humility before the divine.

Ritual and ceremony in historical pantheism.

Most pantheists have emerged from specific religions and have

practised

the normal rituals of that religion.Some pantheist groups have practised their own special rituals - especially the sexual pantheists like the Tantric Buddhists, or the Nicolaitan Gnostics, or the Brethren of the Free Spirit.

But the largest school of pantheists in history, the Stoics, had no ceremonies or rituals as far as is known. Most of them would have taken part in the traditional rites of the Greek and Roman religions, though they probably did not believe in them, or regarded them as symbolic.

Stoicism was primarily a school and a system of philosophy and ethics. Its practice was limited to the thinking of one's thoughts and the living of one's life. The only public expression was philosophical discussion and writing.

Ritual in modern pantheism.

Modern pantheism is not just a philosophy. It is a true religion,

in

the

sense of religio - a binding: a deeply emotional outlook that binds

one's

feelings, thoughts and actions.Pantheism does not need ritual for any primitive magical or egotistical purpose. It accepts nature and the universe in their full reality, and allays anxiety through that acceptance, not through ritual. It does not believe that events or the complexion of the universe or the world can be influenced by prayer or magic.

Yet ceremony can be helpful in pantheism:

- To express our reverence for nature and the universe.

- To strengthen our understanding of the tight links between self,

nature and cosmos.

- To see human life as part of the natural cycle.

- To celebrate the beauty of nature and the universe.

- To strengthen our beliefs.

- To provide mental support at times of stress.

- To provide mutual social support in our beliefs.

- As a daily therapy.

Remembering our place.

It is all too easy to forget our place in the universe: easy to

forget

that we dwell on a planet that turns once a day on its tilted axis and

wheels

around the sun once a year, and is circled by its own large moon.All life on earth evolved in the context of these cyclical rhythms, and still bears their imprint in biological cycles of day and night, waking and sleep, growth and rest, and the rise and fall of tides.

It's just as easy to forget our place in nature - to forget that we depend on plants for the oxygen we respire, just as they depend on animals for the carbon dioxide they breathe. Easy to forget that we are part of a mass of complex ecological cycles - many of which, indeed, we are only just learning about.

And it matters if we forget that we are part of nature and part of the universe. For if we do, we may imagine that we are independent of the rest of nature when we are not. We may develop an arrogance and an indifference towards nature, an assumption that we are her masters and can control her as we please.

Pantheist ceremony stresses the moments of significant connection between ourselves and nature, ourselves and the dynamic solar system. Ceremony reminds us of our links to nature, our dependence on nature.

Sacred time, sacred space.

Every moment of life is meaningful. Every moment is intrinsically

as

important as every other. But there are certain moments in the year

which

represent transitions and shifts in the cycles of nature and the solar

system:

moments of peaks or troughs in the endless waves of change.Many of Christianity's central rituals were taken from the ancient annual cycle. These were celebrated in rival religions such as the worship of Sol Invictus ("the unconquered sun"), and appropriated by Christianity to increase its appeal. Christmas, for example, coincides with the ancient Winter solstice, Easter with the spring equinox modulated by the lunar cycle.

But Christianity has forgotten the roots of what it celebrates. Its ritual has lost the connection with nature.

Pantheist ceremony reestablishes that connection.

The central Pantheist ceremonies of the year focus on the solar cycle, the sequence of seasons caused by the earth's tilt on her axis.

- On March 21, pantheists in the Northern hemisphere celebrate

the

spring equinox, the beginning of growth in plants and breeding among

animals.

- On June 21 we celebrate the summer solstice, the sun's highest

point

in the sky each year.

- On September 21, we celebrate the autumn equinox and the

harvesting

of fruits.

- On December 21 the birth of the new solar year.

The sequence or character of these transitions varies from one part of the globe to another. Pantheist celebrations should take account of this so as to be attuned to the transitions locally. In the southern hemisphere the sequence comes in the same order, but advanced or deferred by six months. Pantheists in tropical climates with less dramatic seasonal variations may choose to celebrate the arrival of the rains, or the dry season, or the cycle of particular plants.

In addition we may choose to celebrate certain days of the agricultural cycle: the planting and the harvesting of the staple crop, for example.

|

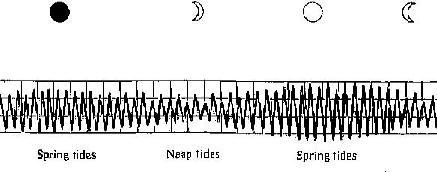

Pantheists also celebrate the monthly lunar cycle, the dance of the moon with earth and sun. The moon is closely linked to life on earth through the daily rise and fall of tides, and the monthly sequence of spring tides and neap tides [see chart above]. Tides are strongest at full moon - when our satellite is on the opposite side of the earth from the sun - and at new moon, when it is on the same side, and the gravity of moon and sun are pulling in the same direction. At half moon tides they are weakest.

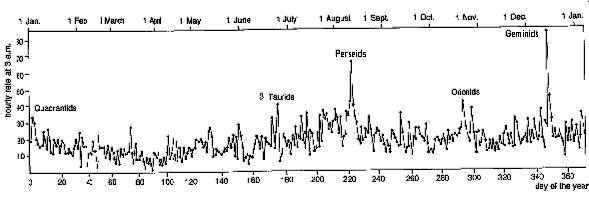

Given clear skies we may also celebrate certain times in the year when there are the strongest falls of shooting stars. These occur as the earth crosses the orbit of clouds of meteors - especially the Perseids, peaking in early August, and the Geminids, peaking in the second week in December [see chart below]. The place where ceremonies are held is important for their effect. Wherever possible they should be held in the midst of nature. The shooting star celebration should be held in areas of low light pollution to witness the spectacle against the backdrop of the brilliant cosmos.

|

Grounding.

The above ceremonies can be performed in any size of group from

small

to

large, or even by a single individual.The cycle of the earth through night and day forms the basis for daily ceremony. Pantheists should try to celebrate their connection with earth and cosmos not less than twice a day, at sunrise or on rising, and at sunset and or on retiring.

These moments can be moments of celebration and of grounding or meditation - moments in which we become conscious of our personal participation in the divinity of the universe, our nature as parts of a whole, as beings made of the same matter as the whole (see Mystical union with reality). At these moments we may greet the sun, or gaze into a flame, or hold a favourite pebble or shell.

Such moments can also be deeply therapeutic, placing your personal problems in perspective, reminding you that apart from your problems you have an ongoing, permanent and unshakable participation in the divine Reality.

Rites of passage.

Just like the course of the year, the course of a human life has

sacred

times. These too are transitions: passages from death to life, and life

to

death, and the committed linking in marriage of two individuals into a

couple,

are the most important. These are celebrated in all religions, and by

civil

law.Pantheists should develop their own ceremonies for child naming, marriage and burial. They should serve to remind us at these times of our place in nature and the universe, and in the natural cycles of birth and death. Because death is perhaps the most critical of these, the one that can arouse the greatest anxiety, there is a separate page devoted to natural death.

Spontaneous expression.

The word ritual implies repetition according to rigid rules.

Ritual that is repeated without variation - like the endless reciting

of prayers - degenerates into form whose meaning has been forgotten.Ritual that allows no space for personal expression, instead of celebrating divinity, can actually block the view of divinity and make the form seem more important than the content.

This is why in the case of pantheism it is better to use the words ceremony or celebration, rather than ritual. A ceremony is a serious occasion - serious not in the sense of without fun, but in the sense of marking a very special quality about the time and place.

This does not mean that the same sacred time and place must always be celebrated in the same way. Modern wedding ceremonies, for example, can take many forms, often designed by the participants. But they are still ceremonies.

Therefore there should always be an element of spontaneity about pantheist celebration - an element chosen by the participants, rather than imposed from outside.

Of course there is no form of compulsion about pantheist ceremony. No church hierarchy, no invisible God will punish you if you do not observe sacred times. But you yourself will miss a chance to reconnect with nature and the universe, in a charged way, at moments of especial significance in the cycles of the year.

Realities, not symbols.

The purpose of pantheist ceremony is to celebrate the universe and nature and remind us of our place in them. If it should ever obscure the underlying reality, then it would be working against its own purpose.

Therefore pantheist ceremony should always be transparent to the reality that it celebrates. Its purpose is to deepen perception and connection - not to stand in their place.

SCIENTIFIC PANTHEISM

is the belief that the universe and nature are divine.It fuses religion and science, and concern for humans with concern for nature.

It provides the most realistic concept of life after death,

and the most solid basis for environmental ethics.

It is a religion that requires no faith other than common sense,

no revelation other than open eyes and a mind open to evidence,

no guru other than your own self.

For an outline, see Basic principles of scientific pantheism.

Top.

Top.

Scientific pantheism: index.

|

If you would like to spread the message please include a link to Scientific Pantheism in your pages and make sure your pages are indexed by the main engines.

Suggestions, comments, criticisms to: Paul Harrison, e-mail: pan(at)(this domain)

© Paul Harrison 1996.